Sitting atop my blog to-do list were three items: a major revision to my query letter, a post on character agency, and promote my novel Wynde. The query letter revisions resulted in much blank staring at the screen, while character agency and the newly finished manuscript for Wynde dominate my thoughts. Agency was never far from my mind as I created my heroine’s story, and I have been working on these ideas for a post since before I visited Coffee With Kenobi last month. On that podcast, I used two recent superhero movies to highlight how agency comes into play, and how it can weaken or strengthen a character.

The word “agency” can have a variety of meanings depending on the context. For purposes of this post, I’m referring specifically to the agency of a character. Characters with agency make decisions that are consistent with their personality within the confines of the story. No character can be in control of the situation, much less her ultimate destiny, at all times. An author’s job is to ensure that when the character can make a choice – whether it’s good or bad, wise or foolish, in service of her destiny or away from it – she does it because it is a plausible reaction from the character’s perspective as the audience understands her. Joss Whedon has made this distinction quite often when talking about writing – when characters serve the plot, the story’s fabric starts to fray.

In Marvel’s The Avengers, Black Widow a/k/a Natasha Romanoff is introduced to the audience bound and gagged. Heroic characters, male or female, have to be put in situations that are beyond their control; otherwise the villain will not appear as a big enough threat to create a sense of peril. This fear for the hero in turn drives the emotional reaction. During the course of her interrogation, Agent Coulson calls one of the thug’s phones and asks to speak to Natasha. Her dialogue quickly establishes that she is exactly where she wants to be. In a matter of seconds, Natasha frees herself and overpowers the entire group of thugs. Over the course of the movie, Natasha uses her femininity and her troubled past as vulnerabilities that she reverses into strengths. Director and writer Whedon is exceptional at this across his body of work. A number of times she manipulates characters into doing what she wants them to do: first with her captors, who believed her helpless; later with good guy Hulk, to whom she appears as unarmed and demurely attractive; and finally the villain Loki, who spouts off a monologue that appears to crush Natasha emotionally as he reveals his plan to use Hulk against the S.H.I.E.L.D. team. As with her initial captors, though, Black Widow chose freely to submit to the painful experience in order to assist her team by obtaining the information they needed to understand the threat against them. She is victimized in the scene, suffering emotionally, yet it creates a powerful statement about her character. In the ending sequence superhero Iron Man suffers physical trauma in order to allow his teammates to succeed. In both cases, the characters have free will to choose the self-sacrifice and it is plausible from the audience’s perspective that they would make such a choice. This establishes their agency within the story.

In Marvel’s The Avengers, Black Widow a/k/a Natasha Romanoff is introduced to the audience bound and gagged. Heroic characters, male or female, have to be put in situations that are beyond their control; otherwise the villain will not appear as a big enough threat to create a sense of peril. This fear for the hero in turn drives the emotional reaction. During the course of her interrogation, Agent Coulson calls one of the thug’s phones and asks to speak to Natasha. Her dialogue quickly establishes that she is exactly where she wants to be. In a matter of seconds, Natasha frees herself and overpowers the entire group of thugs. Over the course of the movie, Natasha uses her femininity and her troubled past as vulnerabilities that she reverses into strengths. Director and writer Whedon is exceptional at this across his body of work. A number of times she manipulates characters into doing what she wants them to do: first with her captors, who believed her helpless; later with good guy Hulk, to whom she appears as unarmed and demurely attractive; and finally the villain Loki, who spouts off a monologue that appears to crush Natasha emotionally as he reveals his plan to use Hulk against the S.H.I.E.L.D. team. As with her initial captors, though, Black Widow chose freely to submit to the painful experience in order to assist her team by obtaining the information they needed to understand the threat against them. She is victimized in the scene, suffering emotionally, yet it creates a powerful statement about her character. In the ending sequence superhero Iron Man suffers physical trauma in order to allow his teammates to succeed. In both cases, the characters have free will to choose the self-sacrifice and it is plausible from the audience’s perspective that they would make such a choice. This establishes their agency within the story.

In Man of Steel, Lois Lane first appears on-screen making a derisive remark about comparing penis sizes and invoking her journalism Pulitzer Prize to male military authority figures. The dialogue is meant to establish her strength and her parity among the male characters. In the second act, though, she is taken captive by General Zod alongside Superman. The consciousness of Jor-El existing in Zod’s ship appears to Lois and takes charge: opening doors, telling her how to duck to avoid a shot or a punch from a villain, and finally delivering the explanation about the means to defeat Zod before ejecting her out in an escape pod, which his son must chase after. While Lois is taken captive by superbeings, it was the plot (and thus the director and screenwriter) that put her free will in a cage. A capable woman might not defeat a Kryptonian in single combat, but a duck to avoid a shot or a slip of her head to avoid a punch to the face because she saw it coming is most certainly possible. Lois loses her agency. After establishing her as tough, smart, and feisty, she uses none of these resources when taken captive. Instead she is just ushered along by a long-dead being that Lois the skeptical reporter should have no reason to trust. Holding the key to defeating Zod’s attacking forces in her mind, Lois serves as a plot device in the third act; to be fair, every other character that doesn’t have a supersuit serves as a plot device as well. A few adjustments in the story would have revealed Lois capable and competent much more effectively and created agency for the character throughout.

In Man of Steel, Lois Lane first appears on-screen making a derisive remark about comparing penis sizes and invoking her journalism Pulitzer Prize to male military authority figures. The dialogue is meant to establish her strength and her parity among the male characters. In the second act, though, she is taken captive by General Zod alongside Superman. The consciousness of Jor-El existing in Zod’s ship appears to Lois and takes charge: opening doors, telling her how to duck to avoid a shot or a punch from a villain, and finally delivering the explanation about the means to defeat Zod before ejecting her out in an escape pod, which his son must chase after. While Lois is taken captive by superbeings, it was the plot (and thus the director and screenwriter) that put her free will in a cage. A capable woman might not defeat a Kryptonian in single combat, but a duck to avoid a shot or a slip of her head to avoid a punch to the face because she saw it coming is most certainly possible. Lois loses her agency. After establishing her as tough, smart, and feisty, she uses none of these resources when taken captive. Instead she is just ushered along by a long-dead being that Lois the skeptical reporter should have no reason to trust. Holding the key to defeating Zod’s attacking forces in her mind, Lois serves as a plot device in the third act; to be fair, every other character that doesn’t have a supersuit serves as a plot device as well. A few adjustments in the story would have revealed Lois capable and competent much more effectively and created agency for the character throughout.

Later in the discussion on Coffee With Kenobi, the conversation turned to Padmé’s confrontation with Anakin on Mustafar. In my Star Wars Insider #142 article, I elaborated on the many reasons Padmé hopes and believes she could turn Anakin back to the light. When Obi-Wan appears from within her starship, though, Anakin’s rage consumes him and Force choking of his wife ensues. One of Padmé’s greatest strengths – her words – are stripped from her. Dan and Corey asked if Obi-Wan had taken away Padmé’s  agency by interceding, and I answered “no.” True, Obi-Wan sneaks aboard her ship and appears at an inopportune moment – but within his own worldview he sees Anakin turned Sith Lord as a grave threat, one that not even Padmé can stop. He has seen the video images of the dead younglings; he knows that Anakin has lost the ability to think reasonably. Earlier, by refusing to tell Obi-Wan where Anakin was, Padmé had tried to prevent Obi-Wan from acting against Anakin. In the end, Obi-Wan’s arrival results in tragic consequences for all three characters, and that is something that must happen in storytelling. So long as Anakin, Padmé, and Obi-Wan are taking actions that are reasonable given what has been established by the story, they maintain agency.

agency by interceding, and I answered “no.” True, Obi-Wan sneaks aboard her ship and appears at an inopportune moment – but within his own worldview he sees Anakin turned Sith Lord as a grave threat, one that not even Padmé can stop. He has seen the video images of the dead younglings; he knows that Anakin has lost the ability to think reasonably. Earlier, by refusing to tell Obi-Wan where Anakin was, Padmé had tried to prevent Obi-Wan from acting against Anakin. In the end, Obi-Wan’s arrival results in tragic consequences for all three characters, and that is something that must happen in storytelling. So long as Anakin, Padmé, and Obi-Wan are taking actions that are reasonable given what has been established by the story, they maintain agency.

Another instance in Revenge of the Sith, however, does create the “oh no, she wouldn’t do that” moment. It is the line of dialogue from the medical droid telling Yoda and Obi-Wan that Padmé has lost the will to live. In a saga that had otherwise shown Padmé as empowered and fighting to the bitter end, many have expressed unease with the notion that Padmé would simply give up. Mothers in particular often describe an inability to relate to this moment in the story. It occurs in the closing moments of a tragic arc, when emotions are high for the characters and the audience. In my Star Wars Insider article on Padmé I propose that the statement from the droid might be wrong, but that doesn’t mitigate the fact that the reaction from the audience creates an issue with character agency. Most importantly, it establishes the point that agency is a highly contextual topic. This is why it is important for storytellers to understand the audience as well as the characters.

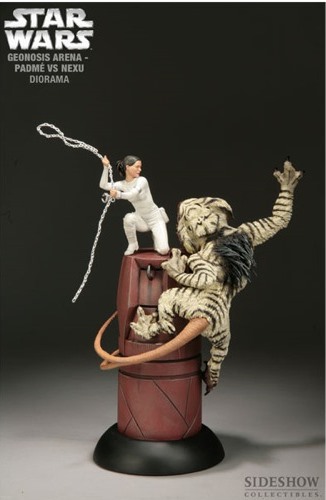

The Geonosian arena scene from Attack of the Clones highlights how a story can effectively weave together a character’s desires, fears, strengths, and weaknesses and maintain a character’s agency. Padmé’s declaration of love, although a bit awkward in its delivery, is given of her own free will at a moment when she is unsure of her fate. Ultimately, the tragedy of the Prequel Trilogy is both Padmé’s and Anakin’s, and while love is a temptation off both their paths – hers as a Senator and his as a Jedi – Padmé does find strength in loving Anakin, and vice versa. Immediately upon spilling her heart, thus opening herself up to potential vulnerabilities, Padmé shows remarkable poise as she orchestrates her own escape from the chains that bind her to the column. Jedi Obi-Wan and Anakin are still bickering bantering as she starts climbing up. As she battles the nexu, it strikes her in the back and her shirt is torn off to expose her entire midriff. While this is a flawed moment in the execution of her story, it’s not about agency within the story but rather objectification outside the story. Although lack of agency and objectification are both negatives in the portrayal of female characters, they are different issues that often get lumped together. Exposing Padmé’s bare midriff objectified her because it didn’t serve any storytelling purpose within the narrative, but it didn’t deprive her actions and decisions on Geonosis of agency. For either flaw, though, it comes back to asking the storytellers, “Did you need to do that?” Often times, this kind of decision appears to fall in the category of “not thought out.”

The Geonosian arena scene from Attack of the Clones highlights how a story can effectively weave together a character’s desires, fears, strengths, and weaknesses and maintain a character’s agency. Padmé’s declaration of love, although a bit awkward in its delivery, is given of her own free will at a moment when she is unsure of her fate. Ultimately, the tragedy of the Prequel Trilogy is both Padmé’s and Anakin’s, and while love is a temptation off both their paths – hers as a Senator and his as a Jedi – Padmé does find strength in loving Anakin, and vice versa. Immediately upon spilling her heart, thus opening herself up to potential vulnerabilities, Padmé shows remarkable poise as she orchestrates her own escape from the chains that bind her to the column. Jedi Obi-Wan and Anakin are still bickering bantering as she starts climbing up. As she battles the nexu, it strikes her in the back and her shirt is torn off to expose her entire midriff. While this is a flawed moment in the execution of her story, it’s not about agency within the story but rather objectification outside the story. Although lack of agency and objectification are both negatives in the portrayal of female characters, they are different issues that often get lumped together. Exposing Padmé’s bare midriff objectified her because it didn’t serve any storytelling purpose within the narrative, but it didn’t deprive her actions and decisions on Geonosis of agency. For either flaw, though, it comes back to asking the storytellers, “Did you need to do that?” Often times, this kind of decision appears to fall in the category of “not thought out.”

In my post “Does Slave Leia Weaken or Empower Women?” I explain how the “concrete bikini,” as Carrie Fisher has dubbed it, does fits into the storytelling narrative of Return of the Jedi. On the other hand, Star Wars marketing and pop culture at times have exploited the imagery in ways that objectify Leia and Fisher that are disconnected from the narrative purpose.

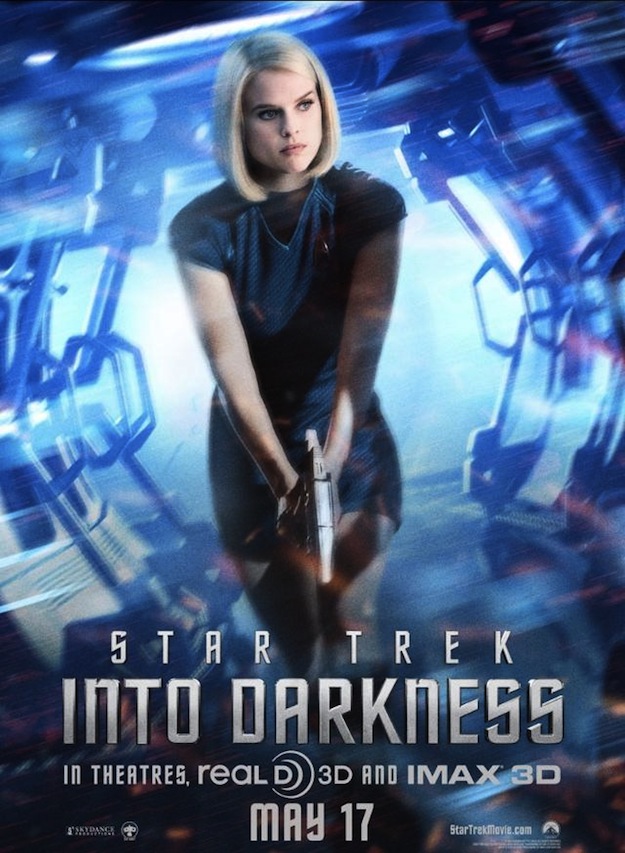

On the other end of the spectrum, the much-criticized Carol Marcus bra scene in Star Trek Into Darkness creates a situation of undress for a female character that both removes her agency and creates objectification. Kirk, the hero, ignores her request to look away while she changes. In the real world this is sexual harassment, which is an issue that is currently plaguing the United States Armed Forces. So either Starfleet isn’t quite at the level of equality Star Trek purports it to be, or the writers have created a situation where Kirk will be court-martialed imminently after the movie’s conclusion – or this was just one of those “not thought out” storytelling moments that would make a good objectifying trailer tease.

This is not the prominent visual of Carol Marcus.

Despite my disappointment in that scene, director J.J. Abrams typically has been one of the storytellers who does a good job of maintaining the agency of female characters even as he runs them through the ringer. As a director, producer, and writer, he has helped bring to life characters like Sidney Bristow from Alias, Olivia Dunham, Astrid Farnsworth, Nina Sharp from Fringe, Kate Austen, Sun-Hwa Kwan, and Juliet Burke from Lost. These women ranged from heroic to conflicted and everywhere in between. They were also shown as flawed, with weaknesses that were strengths and strengths that could be exploited as weaknesses. Many of these characters were beautiful, even sexy. The ladies of Lost for the most part were depicted in primitive living conditions, without benefit of makeup or hairstyling. Olivia Dunham was rarely shown with more than a touch of makeup. That’s why the Marcus’ bra scene – and Star Trek Into Darkness costume design that put the female Starfleet officers in skirts and the men in pants – seems so unnecessary. As a storyteller, Abrams’ work has proven he doesn’t need to strip his female characters of agency or pander to the male gaze to get people to pay attention to his product.

Since the Buffy the Vampire Slayer days, Joss Whedon also has been setting a high bar for balancing creating sexual characters while allowing them to maintain agency and avoid exploitation. While images like Carol Marcus in a bra, Padmé in her nexu-created mid-riff, and Leia in a concrete bikini often give feminists reason to raise an eyebrow,  Whedon has made some pretty bold storytelling choices regarding his female characters that are widely accepted and embraced by feminists. In Firefly, Inara is a Companion, a high-class courtesan. Within the scope of the worldbuilding and in the way the character carries herself and how other characters deal with her, Inara is treated with respect. The show’s main protagonist, Mal Reynolds, who has feelings for the Companion, on multiple occasions calls Inara “whore.” Yet he still remains beloved and well-regarded, and Whedon is still a feminist. Within the scope of the story, the insults and how Inara reacts create compelling lessons about how individuals interact with one another.

Whedon has made some pretty bold storytelling choices regarding his female characters that are widely accepted and embraced by feminists. In Firefly, Inara is a Companion, a high-class courtesan. Within the scope of the worldbuilding and in the way the character carries herself and how other characters deal with her, Inara is treated with respect. The show’s main protagonist, Mal Reynolds, who has feelings for the Companion, on multiple occasions calls Inara “whore.” Yet he still remains beloved and well-regarded, and Whedon is still a feminist. Within the scope of the story, the insults and how Inara reacts create compelling lessons about how individuals interact with one another.

Interestingly, Inara’s character is one who is trained to manipulate people, often by sexual motivations, but she uses other means as well. Manipulation is one of Black Widow’s key character traits, too – just as it is for Nick Fury and Agent Coulson, who are portrayed doing devious things to get their desired results. Manipulating a character isn’t removing their agency; manipulation is altering a character’s worldview. In the Prequel Trilogy, Palpatine manipulates Anakin’s worldview, and really the worldview of the Jedi Order too. The Jedi Council, in turn, manipulates Anakin as well. In that regard, Lucas did a masterful job of crafting Anakin’s fall from grace in a believable way. No one forced him down the path to the dark side – he might have been misled about the stakes and his options, but Anakin still made his own choices.

Most importantly, agency is about free will and making choices, not the outcomes that result. Bad things happening to characters does not equate to a lack of agency; good things can happen to a character and remove her agency. As I was writing this post I realized the query process illustrates this point rather effectively. Let’s tell a story – Agent Hunt – about a woman who wants her finished manuscript published. Author A is established as a hard-working woman committed to her family and job. In her spare time, she diligently reads up on literary agents, crafts query letters that fit each agent based on the limited information available, and polishes the queries carefully before sending them off. Agents B, C, and D receive these lovingly crafted petitions for representation. Unfortunately for A, perhaps B is really looking for an urban fantasy, C thinks mystery pulp is all the publishing houses are interested in, and D just didn’t connect with the story pitch. Despite the protagonist’s efforts to control the situation to the best of her ability, A hasn’t succeeded. While this might be called an unfortunate turn of events, no one has taken away A’s agency.

Good storytellers are able to distill their craft into understandable morsels. As a tutor I found that simplifying was the easiest way to teach a complicated subject. Once a person comprehends the basics, then you can start layering on complexities. After that it takes practice to hone ability. In discussing storytelling, all the experts say “know where you’re going.” This means have a beginning and an ending, which creates a middle – or rather, the plot. Then the experts say “beware of the power of the plot to ruin your characterization.” Balancing the two is not simple. The art of storytelling is creating the framework – I want my character to go from Point A to Point B, thematically and objectively – and then allowing them to take the journey. Doing it well takes a lot of practice, just like mastering an academic subject or athletic endeavor. The big question for characterization to always keep in mind is this: Is the character’s action or decision credible for the character to make given what the audience knows or will know?

Obi-Wan Kenobi: Master of Manipulation

Agency was actually the one area that I kept revisiting when writing my novel Wynde. Numerous people manipulate Vespa over the course of the story, and I worried about that. Watching A New Hope, Revenge of the Sith, The Avengers, and Firefly reruns, where a lot of manipulation happens, helped me gain back my confidence in my own storytelling choices. Back to my Agent Hunt example: so long as Author A is doing something that makes sense from our understanding of her, then bad things still may happen. Allowing characters to manipulate Vespa doesn’t take her agency away, as along as she maintains control of the choices she can. Given that Vespa is young and naïve amid a cast of seasoned politicians and career military officers, the story would be a failure if she wasn’t outmaneuvered repeatedly by the far more experienced adults around her. But that doesn’t take away from the fact that several of the key choices Vespa makes are the ones that ultimately shape the entire course of the story, and certainly her own destiny within the tale. One of the best dynamics in The Avengers, for example, was how each character shifted other characters’ perspectives as they interacted, driving them toward choices they likely would have made differently acting in isolation. Another great example of characters interacting to affect one another in this way is Toy Story 3 by Episode VII screenwriter Michael Arndt. It isn’t an easy process to achieve the end result, which is probably why we hear about so many writers with notecards that allow them to adjust and tweak their plot structure as they tear their hair out.

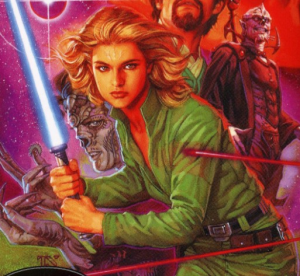

Within Star Wars, the issue of agency comes up from time to time as more stories unfold in the galaxy far, far away – and not just for female characters, although that has been a recurring problem, but for male characters, too. Canon and characterization have had more variation in universes where multiple alternate realities exist, such as Marvel or DC Comics, but as their movies begin to reach a wider audience the main superheroes will become part of a collective consciousness, and the storytellers will have less wiggle room with characters. Marvel’s phased program looks to be a good remedy for this problem, while DC has already had some difficulty with Man of Steel veering away from some fan’s expectations about who Superman is supposed to be. The Star Wars Expanded Universe is actually a good case study in how repeated headlining of a heroic character like Luke Skywalker can result in diminishing audiences as stories stray from the collective consciousness that is based upon a cinematic universe.

Within Star Wars, the issue of agency comes up from time to time as more stories unfold in the galaxy far, far away – and not just for female characters, although that has been a recurring problem, but for male characters, too. Canon and characterization have had more variation in universes where multiple alternate realities exist, such as Marvel or DC Comics, but as their movies begin to reach a wider audience the main superheroes will become part of a collective consciousness, and the storytellers will have less wiggle room with characters. Marvel’s phased program looks to be a good remedy for this problem, while DC has already had some difficulty with Man of Steel veering away from some fan’s expectations about who Superman is supposed to be. The Star Wars Expanded Universe is actually a good case study in how repeated headlining of a heroic character like Luke Skywalker can result in diminishing audiences as stories stray from the collective consciousness that is based upon a cinematic universe.

In Star Wars and beyond, creating effective stories in a shared universe requires balance. The greater the success of a franchise, the stronger the collective understanding of its characters becomes. The creative team’s goal is to deliver something unexpected in a universe the audience knows very well and that they are paying for. This requires that the creative team have a detailed understanding of the fans, their passions, and their expectations, so that their story can give the customers a tale that delivers on the promise the franchise offered its fans. Stories that serve individual creator’s id are always in the greatest danger of affecting character agency. So then, the final question to ask as a writer is: Am I doing this to my character for me, or in service of the character and the story?

Related Posts:

- Coffee With Kenobi Discusses the Ladies of Star Wars

- Whedon on Nerdist: Toy Story to Buffy and Beyond

- Abrams Helms Episode VII: A Fangirl’s Thoughts

- Feige on Marvel Unified Universe

- Fangirls Around the Web: San Diego Comic-Con 2013 Edition – Part One: Star Wars

- Star Wars Insider #142

- Does Slave Leia Weaken or Empower Women?

- Feminism and Star Wars: A Discussion of the Sexualization of Female Characters

Tricia Barr recently told a friend that writing a novel is a marathon, the query process is tackling Mount Midoriyama after running the marathon, and the nail-biting wait is full of blindsides from ABC’s Wipeout. Like a marathoning American Ninja warrior, Tricia picks herself up out of the mud and keeps going, inspired by her many heroines in fiction and in real life. For Star Wars, storytelling and geek culture discussion, hop over to FANgirl.

For updates on all things FANgirl follow @FANgirlcantina on Twitter or like FANgirl Zone on Facebook. At times she tries the Tumblr.